NEAT SOUTHERN PLANETARIES : 18

He2-90 in Centaurus

I would also like to dedicate this page to my

fellow PNe observers in the Astronomical Society of New South

Wales Inc., Mike Kerr (2006) and Scott Mellish (2011), who,

since this was first written, have now both sadly passed away. Both

had contributed much of their own skills and knowledge to this

article in the NSP Series. There sad loss has been genuinely

difficult for me and my fellow members of the ASNSWI, who miss their

real camaraderie and fellowship.

I have selected another faint and difficult

planetaries near the border of eastern Centaurus and Crux. As

planetaries go, He2-90 may not rank as the most elegant, but it has

the advantage of being quite near to one of the very best examples of

an open star cluster — the absolutely fantastic and true

southern observers delight, the Jewel Box / NGC 4755, which I like to

term Gemma Australis Magnifica; and near the large Coal Sack

dark nebula, just south east of the smallest constellation, Crux.

He2-90 / Sa2-90 / ESO 132-1 / PK 305+1.1 / Wray 16-125 /

PN G305.1+01.4 (13097-6120) is placed 2°SEE from κ Crucis (NGC 4755), but it is not usually

listed in any of the popular catalogues or atlases. First discovered

by Karl Henize in 1964, it is often listed, like in electronic

atlases like Megastar 5.0 — but under the alternative

designation Sa2-90. It best found by using the double star J

Cen / J Centauri / Δ133

(13227-6059), and then 1.6°W. He2-90’s position is not marked in Sky Atlas

2000.0, but if you are using Uranometria 2000.0, the field of the

planetary is marked as a tiny triangle of stars near the bottom of

Map 432 and next to the RA line marked 13h 08m. The

10′×10′ field shows the STScI Image (Figure 1) of

the small planetary, which is west of the triad of stars. This same

triad can be also be seen in the attached field-finder chart in

Figure 2. I attach this chart, as it is essential to find the PNe,

which has a self-imposed 15th magnitude limit, with all stars of

above 10th magnitude have there visual ones displayed.

He2-90 is listed as 13.7p mag and subtends 10 arcsec. I

could not see He2-90 directly using 30cm, but applying averted

vision, reveals the small 4 arcsec star-like ‘blip’, which

magically and unexpectedly disappeared in the O-III

filter! I thought the visual magnitude to be about 14th, and this was

confirmed once I had compared to the star chart. He2-90 is listed as 13.7p mag and subtends 10 arcsec. I

could not see He2-90 directly using 30cm, but applying averted

vision, reveals the small 4 arcsec star-like ‘blip’, which

magically and unexpectedly disappeared in the O-III

filter! I thought the visual magnitude to be about 14th, and this was

confirmed once I had compared to the star chart.

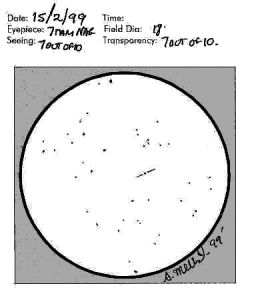

I asked the late-Scott Mellish (Author of the series in the

Journal Universe “Sky-Sketcher’s Post Mortem“) to observe this object with his 40cm.

f/4.7 Dobsonian and 7mm Nagler. The observation was made under 7/10th

seeing and transparency on 15th February 1999, where Scott

states; “Almost

gave up on this one. [He2-90 is] impossible to define as a planetary

without a finder chart. Stellar in appearance, and remains so even in

O-III filter, [and] even 8 arcsec. in size seems far

too large. More like 2 arcsec.”

This truly tiny and faint PNe lies in a profusely starry field. At

first glance you might wonder why I even bothered looking for such an

inelegant object. Honestly, the reason was that I found an

interesting paper specifically on He2-90, and found it has

characteristics quite unlike nearly all known planetaries —

primarily it is very low [O-III] emissions. For

example, if the relative intensity of the Hβ line is 100, then the emissions from the

[O-III] line is O-III=205 (and the

Hα=856) normally, values of

[O-III] would be ten times this value. It is no wonder

the O-III does not work as well as it should!

Fig. 1. He2-90 : Wide Field Colour Image Aladin

12½′×12½′ (left) ;

Fig. 2. He2-90 : Enhanced Narrow Field Image

30″×30″

(right)

Studies of Unusual Planetary He2-90

A diameter stated in the ESO-Strasbourg Catalogue is less

than 10 arcsec, while in the article PASP, 103, 275

(1991) states that the Hα image

finds a circular 12 arcsec disk surrounded by a faint nebula

shell.

One significant difficulty with observations of this PNe is that

it lies a mere 21′NE from the northeast edge of the Coal Sack,

euphemistically called the Black Magellanic Cloud, and the

effect of extinction on the PNe in this region of the sky is

uncertain. The most significant (and only) paper as (of 1999) on

He2-90 was originally produced by Costa, et al. (1993).

It central star is 16.5v±0.25v and 15.6B±0.50B

magnitude. It is believed the PNN is not very luminous, so that the

ultraviolet energies that are required to illuminate the nebulosity

are below par and are not very energetic — hence the poorness

of the viewed PNe. Spectral measures also find the low carbon to

nitrogen ratio of [C/N]=0.3, suggesting the original PNN progenitor

mass is fairly small, perhaps around 0.6-0.7 M⊙. Again the

spectra since the mid-1980s has very low abundances of elements such

as Oxygen, Nitrogen, Sulphur, Neon and Argon, suggesting a low mass

and/or an under-luminous star.

Not many of these objects like this are known, and

include the PNe;

SwSt-1 / He2-377 / PK 001-06.2 / PN G (18162-3052) in

Sagittarius.

Hu2-1 / ARO 100 / PK 051+09.1 / PN G (18498+2051) in

Hercules.

Observations were obtained by Costa et al. (1993) on 11th May 1991

and 4th April 1992, using the 1.6-metre Cassegrain at the National

Astrophysical Observatory, at Brasópolis in Brazil. They

obtained the spectrograph resolution of 0.7nm, with the spectra

surrounding the planetary was taken elsewhere by A. Damineli on 6th

June 1992 surrounding the red Hα

region was accurate to about 0.04nm.

Graph 2 shows the line intensities of the major emissions between

372.7nm. and 733.0nm, using the data from Table 2 of Costa et al.,

p.187 (1993). A comparison spectra of the “standard” PNe is also given. This

clearly shows the deficiency in both [O-III] and

spectra with the other lightweight noble gases. (Compare this with

the information on He2-111 (NSP 16), which has this effect reversed

and an excess of O-III.)

Measuring the Hβ flux and the

diameter of about 6 arcsec, enabling the calculation of distance

using the Shklovsky Method, whose distance is about 1.5kpc. (This is

presently (1999) one of the only estimations for this object!)

Measuring the slight blue-shift of the sharp spectral lines of SII

and NII, finds that the radial velocity of He2-90 moves towards us at

−31 km.s-1. Also from the spectra finds the

expansion gas velocity is presently at a pedestrian 3

km.s-1.

Gleise et al. (1989) has determined the Zanstra temperature

(TZ) of 50,000K, and later by Kaler & Jacoby (1991),

who determined 51,000K. Latest measures of the PNN of He2-90, say

these values maybe about 15% too high.

It appears the that the atmosphere surrounding the PNN is fairly

compact and dense, with the luminosity being some one thousand times

more luminous than the Sun. [log(L★/L⊙) is 3.0] This

confirmed by observations by the IRAS satellite and in the near

infrared (NIR). IRAS observations in 1982 at 100 mm makes He2-90 is

a strong energies or flux PNe at this wavelength, and supports the

NIR observations of the D classification in 1987 — where

the major of visual brightness in these wavelengths come from

circumstellar dust — an uncommon property with PNe. (See NSP

21: NGC 6445 that also shows significant dustiness.)

Hα profiles produced by Damineli

(1992) shows the PNN superwind velocity of

1.050km.s-1.

Note: A discussed in earlier parts of the NSP

series, the velocity of this outflow emanates from the PNN itself. As

the gas radial travels away from the PNN, its mass collides with the

much slower 10.2 km.s-1 atmosphere loss that once occurred

during the Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) stage, and causes the

illumination of gaseous structures that we see in the telescope.

Using Damindi’s (1992) data, Costa

et al. (1993) infer the PNN radii as around 0.38R⊙ or 500,000

km., and the local “speed of

sound” at the top of the photosphere being about 15

km.s-1. For a comparison, the speed of sound at sea level

on Earth is about 0.3 km.s-1 and across the solar

photosphere about 1.2 km.s-1.

Overall, the past evolution of He2-90 and the cause of the very

low abundances remains particularly uncertain, though it is likely

produced by either the low mass progenitor or under luminous star.

References to He2-90

- Costa, de Freitas Pacheco and Maciel “He2-90 : a southern planetary nebulae with

low metal abundances.”, A&A., 276, 184 (1993).

- Damindi, , (1992)

- Gleise, et al., , “

” A&A., 222, 237

(1989)

- Kaler, J., Jacoby, “ ”, AJ., 372, 215 (1991)

- PASP, 103, 275 (1991)

He2-90 Update: 23rd June 1999

Attached is a processed image (Figure 3 — immediately below)

by the late-Mike Kerr which discusses the weird nature of this

planetary. There are few images that I know of that look like this!

The image shows two quite unusual features;

1) The stunning red colouration.

2) The polar "spikes".

There is obviously unusual characteristics with this object, which

reflects the low [O-III] abundance and the low PNN

temperature.

From a private communication by e-mail on the 21st

June 1999 Mike said;

“I’ve got an image for you of He2-90. The image

is 100 arc-seconds square with north up and east to the left.

I produced this ‘true-colour’ image using the narrow band image process I

described at the last (ASNSW) Technical Meeting. The images are from

the Innsbruck University database and are Hα and [O-III] images taken

with ESO’s 3.5-metre New Technology

Telescope in Chile. I have applied a logarithmic scale to the images

to compress the dynamic range and better show both the bright and

faint parts of the object. I assume the two spikes are not part of

the object but are diffraction spikes from the telescope, which have

been enhanced because of my processing.

At the Hα wavelength(s), He2-90

appears to have a bright, circular central disk about 6″ in

diameter surrounded by a fainter circular halo about 14″ in

diameter. [O-III] emission is limited to a central,

stellar-sized disk about 2.5″ in diameter. This would seem to

match pretty well with Scott’s

observation. All in all, quite a strange planetary!”

Figure 3 : He2-90 Imaged by Mike Kerr

Last Update : 24th October 2011

Southern Astronomical Delights ©

(2011)

For any problems with this Website or Document please

e-mail me.

|